We all experience it: when faced with a problem or situation, we come up with a ready, instinctive response, even before we have had a chance to reason about it. This idea, that within us live a fast, instinctive decision-making system and another, slower, intentional one, is called dual process theory: its formalisation in these terms took place in 2003, and has become very popular in the social and cognitive sciences. In its classical formulation, however, it has some aspects that are not fully resolved. We discussed this with Wim De Neys, a cognitive psychologist and research director at the CNRS, at the IMT School during the 2025 edition of SPUDM, a conference focused on research on decision-making processes and the way we reason.

What is the dual process theory

The so-called dual process theory hypothesises that there are two processes, or systems, by which people can produce a thought, decision or judgement. The first, also called 'system 1', is fast, intuitive, heuristic, and comes into action when we respond or decide on things we have done many times and do not need to reason about, e.g. 'how much is two plus two'. The second, 'system 2', on the other hand, is deliberate, slow, reasoned, and sets in motion when there is a need to think and make an effort to find a solution. In this view, phenomena such as prejudice are seen as a 'problem' of system 1, which responds 'on the gut' before system 2 can eventually activate and 'logically' correct the thinking. At the narrative level, the model also works very well, and has in fact become popular: for its theorisation, the psychologist Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. But, to date, it has aspects that are unresolved or in need of adjustment and correction.

Comparing models

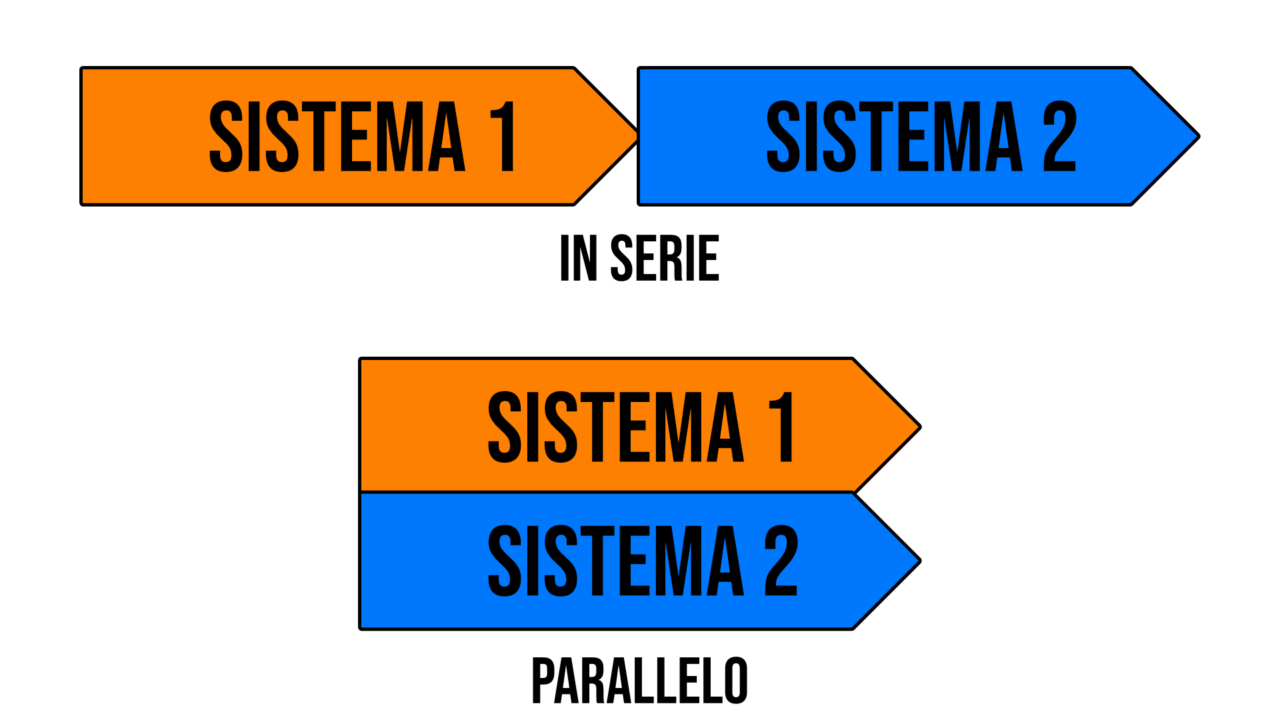

One question the researchers ask is how do the two systems interact with each other? "We have two models, one called serial, the other parallel," explains De Neys. "The serial view says that in the initial phase only system 1 is always activated, and in later phases system 2; while according to the parallel model both are activated at the same time." In itself, the serial model sounds reasonable and 'economical', predicting that the second, more demanding system will not trigger if the first intuitive system can already provide a correct answer. Always using both systems would only be a waste of energy, so system 2 is only triggered when really necessary.

The parallel model, on the other hand, explains the presence of cognitive conflict when people are faced with a problem for which their intuitive answer is wrong or prejudicial. In the serial case, in fact, before the activation of system 2 we should not be able to know that there is something wrong, having only the answer of system 1 at our disposal. Instead, according to various studies over the last twenty years, including some conducted by De Neys himself, when faced with a problem that takes our intuition in the wrong direction, the logical part of our brain is activated anyway: we take longer to respond, our way of observing the problem is different, we detect, in short, the existence of a conflict.

However, the parallel system is also not entirely convincing. The second system should in theory be more energy-intensive and demanding, and in situations of cognitive load or under pressure we should have less energy and/or less time to activate system 2, and thus be less able to detect the cognitive conflict. However, this does not happen, as several studies conducted over the years, including by Neys himself, show, and even under these conditions we are able to detect dissonance.

A new combination

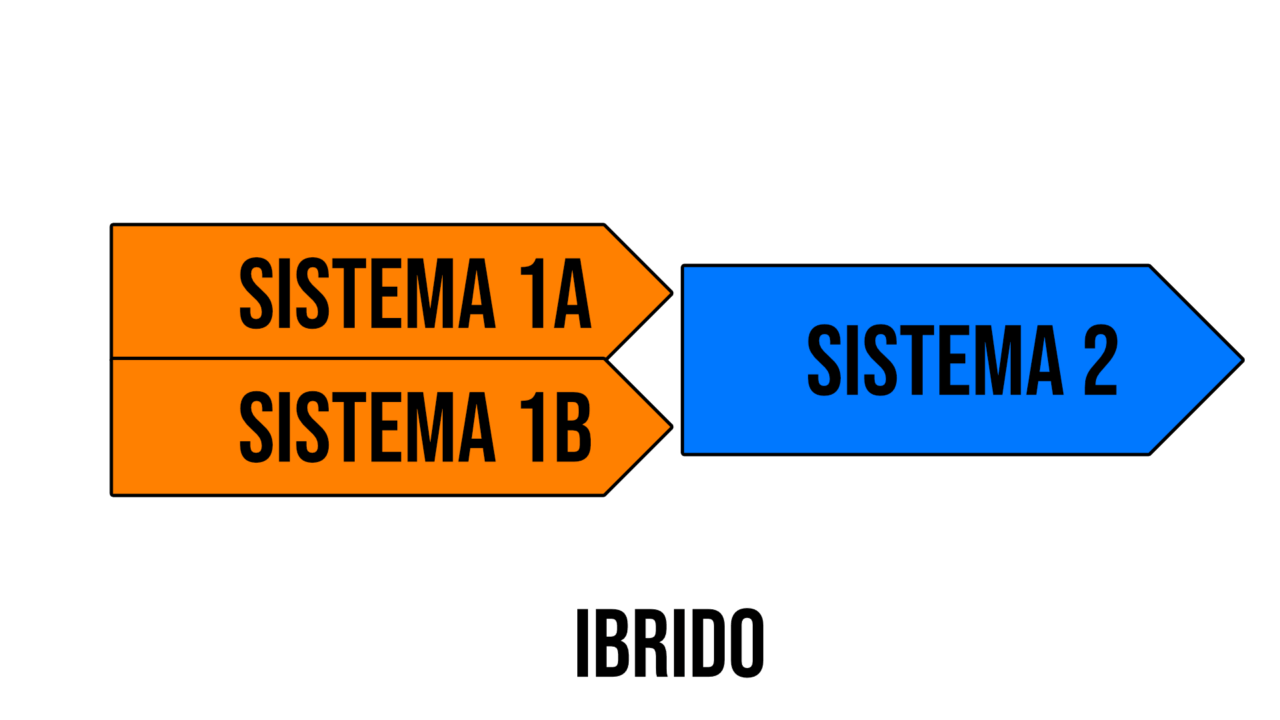

At present, many cognitive scientists therefore think that a hybrid model, based on both old models, is needed to explain our way of reasoning. "Neither of the serial and parallel models alone can explain all the data. What experience suggests is that people already process many basic notions of logic and probability when they are in a purely intuitive mode of reasoning," De Neyes notes. 'You don't necessarily need to activate system 2 to make logical and probabilistic reasoning. Our intuition, in addition to stereotypes, also has such knowledge that we can exploit with system 1."

In the hybrid model, system 2 is activated after system 1 as in the series model. System 1, however, is more complex than the classical one, and is now composed of two subsystems: type A, which is more heuristic, 'gut-based'; and type B, which is more logical. There are in fact intuitive forms of logical reasoning, which we can quickly access and intuitively.

By adopting the hybrid model, we can test other assumptions of the classical dual process theory. One of these concerns the role of system 2, which should allow us to evaluate and possibly correct the initial intuitive response given by system 1.

However, by studying both the immediate response and the reasoned response of people to a deliberately counter-intuitive riddle, the results say something else. Take for example a classic question such as the following: "A bat and a ball cost 1.10 euro together. The bat costs 1 euro more than the ball. How much is the ball?". This type of riddle is deliberately misleading, and in fact the most common intuitive answer (10 cents) is wrong (the correct answer is 5 cents). Most people who get the intuitive answer wrong fail to correct it, even if they think about it; other people manage to correct a wrong intuitive answer; still others answer correctly from the start.

The surprising result is that the people who answer correctly right away are practically twice as many as those who only corrected the answer later. This means that, in most cases, the correct answers come from intuition, rather than from a system 2 correction.

A reason for an insight

If system 2 is not strictly for evaluating and correcting system 1, which can autonomously give correct answers, what is it for? "We observe that even people who generate the correct answer intuitively often engage in a deliberate reasoning process, i.e. they spend time reflecting, but do not need to correct themselves, because their initial answer is already correct. One explanation we propose is that reflection is probably important, but not to correct intuition, but often for different reasons, such as finding an explicit justification for the intuitive response, find the reasons why your thinking is actually correct'.

This process, moreover, often occurs regardless of whether the answer is correct or not. "It is also thought to be a way for people to rationalise incorrect intuitions. Someone with a racial prejudice, for example, will look for 'logical' reasons to support this opinion. Faced with a figure on the detention rate of foreigners, they will perhaps think that foreigners commit more crimes," explains De Neys. 'The fact that people reflect and find justifications does not of course mean that the justification is actually valid and correct. It just means that you look for an explicit reason that can be used in an argument to convince someone."

Preventing prejudice

This kind of reasoning could be at work in the creation and maintenance of prejudice. And so better understanding how it works could also have practical applications, including a new way of thinking about fighting bias. Indeed, in classical attempts to eliminate bias in people, the focus has often been on system 2, trying to strengthen its corrective capacity. If, however, following the new model, the correct answers are mainly given by the intuitive logic of system 1, that is where work needs to be done.

"There is a lot of research trying to find ways to improve people's reasoning, to prevent them from being influenced by prejudice," the researcher explains. "The classical approach typically focuses on making people think more, because the idea is that people don't overcome prejudice because they are stuck in system 1 mode. But our research shows that people who reason spontaneously and correctly usually generate solutions already at an intuitive level. So perhaps what we should do, if we want people to improve in reasoning, is not to make them move from intuitive to deliberate reasoning, but simply to make sure that within their system ihe level of activation of logical intuition is enhanced'.

This idea is supported by some studies analysing de-biasing interventions, where participants watch videos explaining how to behave or react in certain situations. Looking at the tests used to measure prejudice before and after the intervention, where both intuitive and reasoned responses are assessed, an impact is observed already at the intuitive level in retrospective tests. This impact is also not volatile: 'We detected it up to two months after the intervention. The efficacy decreases a little, but it is still an improvement".

This result is only true, however, for relatively simpler problems, where people can draw on elementary logical principles they already know in order to generate the correct answer, and can therefore make them 'automatic' at an intuitive level. "This is however a big step forward, because even if we are talking about simple logical principles, these are still important for example to avoid misinterpreting the efficacy of a vaccine. For other situations, where one does not have the necessary knowledge to internalise, it will be necessary to engage in more deliberate reasoning'.

Jasmine Natalini