Rarely do we think of law in relation to art and fashion. Yet it is precisely law that is present in many aspects of the industry: from the language we use to define fashion and art, to the contracts and regulations that govern their use, to the responsibilities of institutions towards the communities and creators that give life to works.

The work of Felicia Caponigri, Assistant Professor of Law at Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee and author of the podcast A Fashion Law Dinner Party, moves between fashion, art and heritage, exploring how law can help museums, brands and communities share their heritage in a meaningful way.

Can you tell us more about the relationship between art objects and fashion objects?

In many respects, the comparison between fashion objects and works of art is false and misleading. Fashion is not art, mainly because fashion is functional, whereas art is not. We wear fashion on our bodies and connect it deeply to our identity. Fashion may be beautiful, or possess aesthetic qualities and reflect cultural moments like art, but it serves a fundamentally different purpose, closer to our individual and collective identities than the artistic experience. Consequently, legal categories that can apply to both art and fashion operate differently and produce different results.

In the US, for example, fashion is in almost all cases excluded from copyright protection because fashion design is mostly inseparable from an object of use (a dress, bag, etc.). Cultural heritage law also applies differently to art and fashion: we can recognise the cultural interest of a fashion item by the way it reflects the identity of the person who wore it, not just the person who designed it. A work of art can certainly be linked to an artist and a collector, but a fashion object has a radically different purpose, which influences the various forms of concrete protection that law can grant it.

What is the difference between fashion and art objects from the point of view of authenticity?

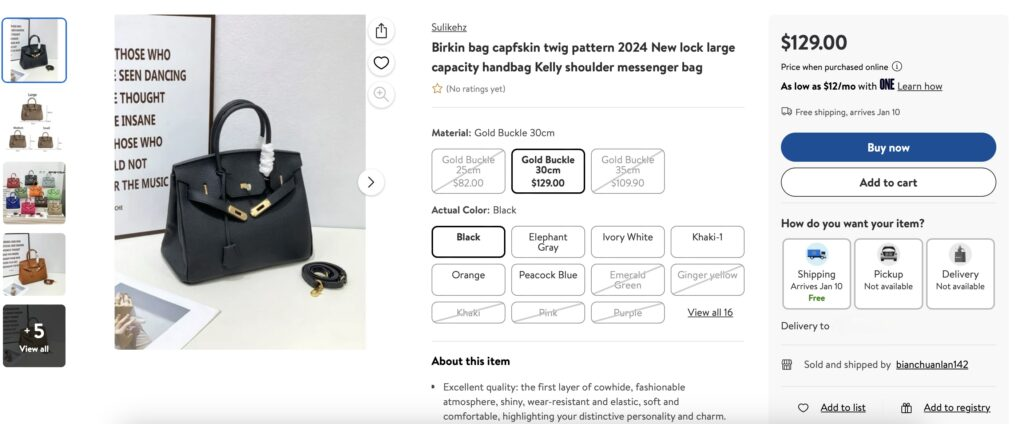

Myth building is an important part of fashion narratives. So too is the blurred boundary between the material origin of a fashion object (the brand or company that produces it and guarantees its commercial value) and its creator (the designer or creative team that comes up with the design or collection concept). To complicate matters further, today brands are no longer the only parties that help define the provenance or, increasingly, the authenticity of a fashion item. Consumers are looking for so-called “dupes”, i.e. products that without being fakes imitate famous products, and redefine what is authentic for them: a counterfeit Birkin bag can be perceived as just as - or even more - “authentic” than a genuine Birkin produced by Hermès.

In your studies, you emphasise how the term “iconic” is more than just a cultural or marketing expression: it also has legal implications that influence the protection and perception of objects, shaping how the law interprets their distinctiveness. In what way?

The concept of iconic has several meanings. Describing a fashion design as iconic can mean that it is famous or popular. “Iconic” can also express a relationship between design as a symbol and its meaning, or present design as an object of veneration, something of great influence and relevance.

All of these meanings certainly have cultural implications: the fame or popularity of a design, its symbolic value and its status in society may be reasons why a design is considered to be of historical or artistic importance, or even - to quote Italian cultural heritage law - an asset with testimonial value for civilisation. At the same time, not all these cultural meanings and implications are reflected in law. Often, before a public body or a museum assesses whether a design has historical or artistic importance from the perspective of cultural heritage law, brands try to protect their designs through trade mark rights.

A trade mark right on a design grants a brand a limited monopoly on a specific message that design communicates to consumers in the marketplace. A registered trade mark on certain parts of the design of the Birkin bag by Hermès, for example, serves to recognise that when consumers see that design on a bag, they understand that Hermès is the manufacturer of the bag, i.e., the material origin of the goods marked with the Birkin design. Through this trade mark right, Hermès can prevent other brands from confusing consumers by producing similar designs of bags on the market. Hermès can even potentially prevent other brands from diluting the message of origin that the design communicates to consumers.

But what is the difference between the iconic nature or status of a design and its ability to communicate the origin of a material good to consumers? As brands organise museum exhibitions, collaborate with curators to present their products and enhance their heritage in communication projects, the iconic status of a design has the potential to expand brand rights to that design. This broadening of brand rights can hinder and weaken the creation of other culturally significant designs in the marketplace.

Collaborations between fashion houses and museums are increasingly frequent. Can you cite real examples, discussed in your studies, where commercial and cultural objectives have intersected?

Today, it is difficult to distinguish between commercial and cultural objectives, as there is indeed considerable overlap. As we know from the Rogers v. Grimaldi, in which American film star Ginger Rogers sued the producers of Federico Fellini's film Ginger and Fred, arguing that the use of her surname improperly implied that she had approved of or was involved in Fellini's film, film titles and other forms of artistic expression have a hybrid nature. Artistic (or cultural) and commercial elements and goals can be inextricably intertwined.

When fashion houses present their collections in a museum, the promotion of a product and the expression of a cultural value inevitably intersect. And this intersection is not necessarily bad! We saw this recently with the presentation of Giorgio Armani's Spring/Summer 2026 collection in the courtyard of the Pinacoteca di Brera: a few metres away from the Armani garment display were paintings from the museum's collection. The presentation of the collection was clearly a cultural moment, given Armani's recent death, and this cultural moment also included a product for sale: fashion.

Similarly, in 2018 Chanel held its parade inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the Temple of Dendur. Ferragamo presented the first fashion show at the Louvre in 2012, an honour bestowed upon him thanks to his sponsorship of an exhibition dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci's painting The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. It is in these circumstances - when fashion shows are part of negotiations to sponsor fashion exhibitions or other cultural activities within the museum - that legal questions begin to arise, and we may feel a certain unease at the otherwise beneficial contamination of culture and commerce.

From a legal point of view, what are the main issues that arise in these partnerships?

The fundamental legal issue is to define the sphere of influence of a museum and a brand. Museums operate in the field of cultural preservation and enhancement. According to codes of ethics and their institutional statutes, museums have duties and obligations towards their public. As the Code of Ethics of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), museums hold their collections in the interest of society and its development; they preserve, interpret and promote cultural heritage; and they collaborate closely with the communities from which the heritage they exhibit originates.

Although fashion brands may also produce and present heritage products, they are for-profit enterprises. They are not cultural institutions, although they may have non-profit branches. Fashion brands care about their bottom line: they want to sell their products, pay employees and suppliers and distribute dividends to shareholders. A fashion brand might, for instance, want to move a work of art into a museum collection to better present its creations. However, this might not be in the museum's interest, or even not be something a museum can do! In such cases, the interests of museums and brands may be opposed. Similarly, although a museum may rent its spaces to raise funds, it is crucial to preserve the public's trust in the museum institution. The Pinacoteca di Brera, for example, despite hosting Armani's Spring/Summer fashion show, cannot be perceived as “Armani's museum”, so to speak.

In your comparison between Italy and the United States, you explore how fashion objects can be considered cultural heritage. For Italian museums exhibiting fashion objects, what legal instruments or documentation are essential to ensure that a fashion object is properly recognised and protected?

Ethical codes - such as the Code of Ethics of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) - can offer all museums guidelines on how to document objects in their collections, including fashion objects. The challenge for Italian museums concerns the legal presumption that can result from the inclusion of a fashion object in their collections. If a fashion object is included in a public museum collection, such as the Costume Gallery of Palazzo Pitti (now the Fashion and Costume Museum), it is automatically presumed to belong to the cultural heritage. Private, for-profit museum collections or archives, on the other hand - such as the internal archive of a brand that lends individual fashion items for various exhibitions - require, under Italian law, a notification accompanied by a declaration of their cultural value in order to be considered cultural heritage.

Sometimes we are confronted with legal fictions or legal anomalies when we see the same fashion object in both the private archive of a for-profit brand and in the collection of a public museum. We may have precise reasons for recognising the cultural value of a garment Brioni in a given context (such as a company archive), but not having those same motivations made explicit in other contexts (such as a public museum). Public museums can do a lot to bridge this gap and to foster the notification and recognition of private fashion collections and archives as cultural heritage, by making explicit in their records and acquisition documents the reasons why a fashion object was included in their collections.

You emphasise the importance of involving communities whose cultural traditions inspire fashion and contemporary art. How can brands collaborate with these communities in a respectful and mutually beneficial way?

A central point to consider is that the difference between brand and community is not so clear-cut. Latinx designers such as Willy Chavarria found their own brands and present collections inspired by the communities of origin they belong to. In this sense, founders can represent their communities and easily collaborate with artisans and designers. Where brands can make mistakes is when their narratives and designs become too distant from the communities they draw inspiration from. Chanel, for example, cannot be criticised for adopting elements of French cultural heritage, but it can be criticised when it organises a fashion show in Texas with models inspired by the Native American community.

Collaborating with communities can be a complex undertaking, given the multifaceted nature of diasporas. Vertical and horizontal power dynamics also influence who can be perceived as the “legitimate” representative of a community and who can be considered by a brand as an appropriate partner to collaborate with. Respectful and mutually beneficial collaborations between brands and communities of origin often imply transparency, a certain economic remuneration, recognition and awareness of the importance of avoiding stereotypes and preconceptions about the cultural heritage of the communities of origin. But who is part of a community of origin is a crucial question. This question seems to be in constant negotiation, especially in the United States, where cultural appropriation of hairstyles or clothing for profit, without any recognition or involvement of the community of origin, is often denounced by many different actors and considered problematic and a source of shame.

Based on your academic and professional experience, what tools or legal practices would you recommend today to a museum or cultural institution wishing to protect and enhance its fashion collections?

I would recommend maintaining an open relationship with brands, but accompanied by a healthy scepticism as to why a brand would want to display its creations in a museum exhibition or donate fashion to a museum collection. For every Giorgio Armani, there is a less culturally relevant brand that may see the museum simply as a marketing opportunity. I would recommend carefully documenting each fashion item that becomes part of the collection and specifying where it comes from and why it is accepted into the museum. This documentation and level of detail can go a long way in helping the public, public bodies and even brands to recognise the cultural importance of fashion pieces, especially in the event that a brand closes, is sold or encounters difficulties in the market. And finally, not to be afraid to confront a brand's intellectual property or to collaborate with designers and artists who may raise intellectual issues, as Mason Rothschild recently did with the project MetaBirkins. A fashion brand does not “own” a museum, regardless of the number of exhibitions it sponsors or the amount of the brand's garments in the museum collection. The responsibility of a museum is towards its public, and the only way to strengthen public trust and recognise cultural heritage is to constantly question and dialogue with the cultural status quo - and this includes the status quo of fashion.

Rebecca Linguanti